PEOPLE

UNDER(WATER) PRESSURE

01 May 2017

Under(water) pressure

Can PIONEER journalist Benita Teo take the pressure and heat to complete a 10m bounce dive in the hyperbaric chamber?

If there is one word for my experience, it will be "naked".

Naked, when I had to lay bare my medical history for assessment. When I had to undergo an exhaustive physical examination, which included blood tests and body fat analysis, to determine my fitness. And when I had to strip down to nothing but a set of 100 percent cotton T-shirt and shorts.

All before I was allowed inside the hyperbaric chamber to do a bounce dive.

All that pressure

This is the story that almost didn't happen. On the morning of my dive, I am raring to get into the pressure chamber at the Naval Hyperbaric Centre. My medical exam results are all good. Until

"Uh, ma'am, your blood pressure is a bit low."

Three more rounds of blood pressure tests later and I'm sitting in the Medical Officer's (MO's) office, wondering if I'll be filling these two pages of the magazine with hand-drawn stick figure pictures. Luckily, he gives me the green light after determining that my blood pressure is within the acceptable range.

That's how stringent the selection process for Underwater Combat Medics (UMs) is. All UM candidates have to undergo a bounce dive -- an underwater dive in a hyperbaric chamber.

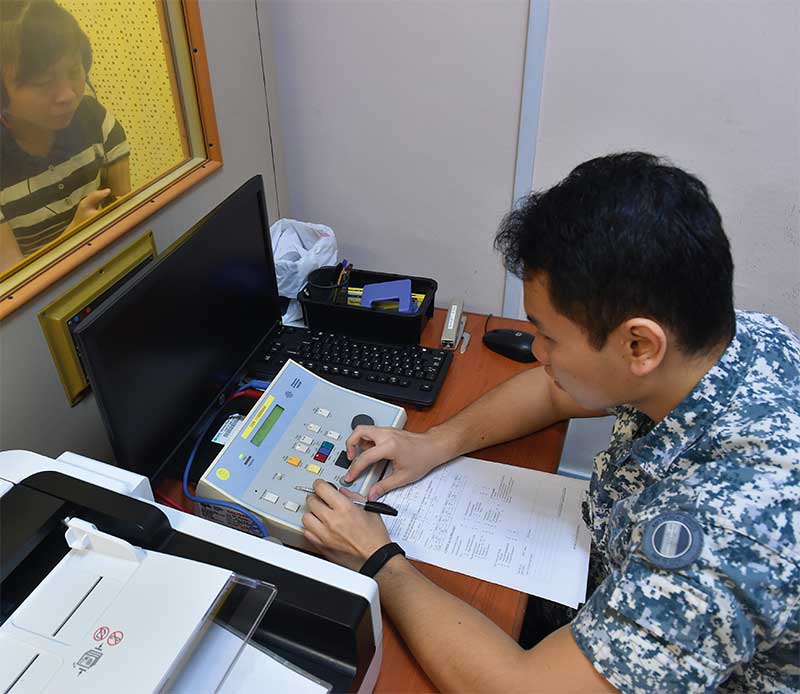

Except that no one's actually getting wet. Air is pumped into the airtight cylinder to simulate a 10m dive underwater. Hyperbaric attendants, who accompany patients in the chamber for treatment, must be able to withstand the pressure changes of "diving" down and back up.

"100% cotton"

At the centre, I'm given a 100 percent cotton T-shirt and shorts to change into, and told to remove my jewellery, contact lenses and footwear.

Ten other submariner hopefuls join me in my dive. Gingerly, I climb into the hyperbaric chamber, a capsule about 3m long, 1.5m wide and 2m high.

It is mostly empty, save for two beds to treat patients with decompression injuries. There is no clutter, to avoid the risk of fire.

Head first

The dive starts off uneventful. But as we go deeper, pressure begins to build up in my ears.

The chamber attendants have instructed us on the valsalva manoeuvre -- blowing our noses while pinching them to relieve the pressure building in our ears.

Doing this brings relief, but the pressure immediately starts up again. And again.

I start to freak out. Despite being exhausted from blowing my nose continually, I can't stop because my ears felt like they were about to explode. Panicking makes my heart race even faster.

I try to count the interval between the build-up: one, two, three, four, five -- blow. By swallowing and taking slower breaths, I'm able to cut down on my nose-blowing and calm down.

When we hit the bottom, the chamber has heated up like a sauna. In just a few minutes, everyone is perspiring and squirming uncomfortably. I wonder how the chamber attendants and MOs can work in here like this for periods of up to four hours at even lower depths of 30 to 50m.

Bare essentials

Slowly, we begin our ascent. This time, we have to get rid of the discomfort in our ears by swallowing. We also have to avoid folding our limbs to keep air bubbles from collecting in our joints.

The bounce up is less uncomfortable, but equally disconcerting. I feel a constant popping sensation in my ears, like an elephant running clumsily across bubble wrap.

Finally, after what feels like hours, the 15-minute dive is over and we "reach the surface". Cool air fills the chamber once more. There is a visible look of relief on all our faces as we breathe in the fresh air.

Having to be stripped down to my bare necessities for this bounce dive, I can only imagine how vulnerable hyperbaric attendants feel at work.

Alone in the chamber with their patients during treatment, they have to work independently, carrying only their most essential medical equipment.

When an emergency happens in the watery depths, the solution is not a simple opening of the chamber doors to escape. They need to use whatever tool they are given to keep themselves and their patients safe until help arrives.

This must be why UMs can wear their skills like badges of honour.

ALSO READ IN PEOPLE

When two hearts set sail together

13 Feb 2026

Naval engineers ME2 Gary Lim and ME2 Audrey Ho share how they navigate love, military service, and (soon) parenthood.

I’ve always got your back

11 Feb 2026

She’s an Army officer, and he’s the (NS)man supporting her dreams. CPT Koh Xinci and 3SG (NS) Nitro Chan share their love story with us – including their unique wedding!

He’s an NSF Commando & medal-winning fencer

28 Jan 2026

His team won gold at the SEA Games 2025, and he hopes to represent Singapore in more competitions to come. Meet fencer CPL Samuel Elijah Robson, who is serving as a Commando during his full-time NS.