TECHNOLOGY

RESTRICTED ACCESS

08 Oct 2012

As DSO National Laboratories marks its 40th anniversary this year, PIONEER journalist Sheena Tan gets a rare tour of three of its laboratories.

"Sorry, that's classified." That was the answer I was expecting when I broached the idea of visiting the DSO labs. After all, the labs, in which technologies to enhance national security are developed, are closely-guarded vaults that most Singaporeans will never set foot in.

Turns out, it never hurts to ask, and I was granted the privilege of checking out what goes on in the labs that house some of Singapore's best kept defence "secrets".

Testing potions

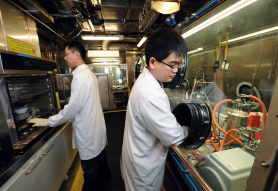

The first place I visited was in a building at Marina Hill, and after walking through what felt like a labyrinth, I entered a chemistry lab.

Describing the work done here, defence scientist Mr Neo Tiong Cheng said: "We use small quantities of toxic chemicals and test them on the protective suits worn by our armed forces in chemical defence. This is to verify the vendors' claims on the efficacy of the protective gear against such agents."

This DSO lab has permission from the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) to use and handle toxic agents.

The OPCW, with headquarters in The Hague, Netherlands, is an inter-governmental organisation that promotes adherence to the Chemical Weapons Convention, which prohibits the use of chemical weapons and requires their destruction.

No escape

Working with such toxicity levels makes it necessary for the lab to have multiple safety measures that protect the scientists from the chemicals they handle.

The highlight of the lab is a glove box, purchased just this year, that allows scientists to slip their hands inside to handle the toxic agents without being exposed to the agents.

In the unlikely event of spillage outside the glove box, the scientists will remove their protective gear. They then head for the shower, located within the lab, for decontamination. Before leaving the lab, hand-held chemical detectors are used to scan for any traces of contamination.

"As a safety measure, we also work in pairs. The one that handles the agents is called the 'dirty hand', while his partner is the 'clean hand'. The clean hand's role is to administer first aid and call for help in emergencies," Mr Neo added.

From the "flyer" to the sky

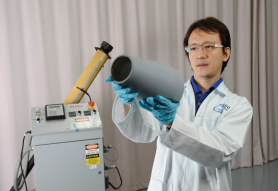

From the potions lab, I moved on to a textile pre-forming lab in Boon Lay. In it were weaving devices, giant spools of hair-like fibre measuring the length of my forearm, and a machine that resembled a Ferris wheel, except that it seemed to be made of yarn.

"This is a braiding machine, but we call it our DSO Flyer, because it looks like the Singapore Flyer, doesn't it?" said Mr Elvin Chia, a DSO composite engineer.

So what does a braiding machine, that joins fibres together, have to do with defence?

Mr Chia explained: "The machine braids and intertwines fibres together into the shapes of the parts that we want. After that, we add resin (think of it as a kind of glue) to harden and turn them into composite structures."

Compared to traditional metals, engineered composites are stiffer, stronger and lighter materials, making them ideally suited for UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) components, and the resulting lighter weight allows the UAV to fly faster and carry more payload, he added.

When asked what was so special about this DSO Flyer, which was assembled and commissioned locally in 2010, Mr Chia replied with a grin: "Well, many countries have simple braiding machines that can create flat or tubular structures, but the one we have has a multi-axis design that allows us to create complicated, asymmetrical structures such as wings and fuselages for UAVs."

With the DSO Flyer, there's no telling what other UAV parts it'll be churning out in a few years.

The heat is on

The last lab I visited was a facility to conduct heat management trials for the Singapore Armed Forces.

The Combat Protection and Performance Programme, located within the DSO building in the National University of Singapore, is a lab in which soldiers undergo trials that test hydration levels, core body temperatures and energy expenditure.

Defence scientist and physiologist Dr Jason Lee elaborated: "The Army is always concerned about heat strain, so it's important for us to understand soldiers' heat profiles in various environmental conditions."

"Here, we study how a soldier's body temperature responds to various climatic conditions during training and operations," he added.

To do that, DSO had an environmental chamber built around 1993, and it remains the only such chamber in Singapore capable of simulating weather conditions from 5 to 60 degrees Celsius, relative humidity between 20 and 95 percent, wind speeds of up to 5m/s and solar radiation of about 1,000 watt per square metre.

That means, one can experience what it feels like to be in the Sahara desert during the day and in Moscow during autumn within that 5m by 5m chamber!

My turn!

In the chamber, scientists measure core body temperature by getting trial participants to ingest a temperature capsule eight hours prior to the trial. This allows the capsule to rest in the colon while the participant's temperature is monitored using a temperature logger.

Participants also put on a metabolic analyser, a mask that aids in the calculation of the amount and the type of energy used, be it from fat or carbohydrates.

They are then asked to walk or run on a treadmill carrying the typical load of a soldier on a mission, as the chamber works to simulate environmental conditions out in the field.

There was no way I was getting out of that lab without trying out the chamber, so Dr Lee got me to put on the metabolic analyser, carry a 10kg field pack and walk on the treadmill, as the temperature in the chamber was pushed to 35 degrees Celsius with a relative humidity of about 70 percent. This was to simulate a route march in a hot and humid jungle.

The first five minutes were fun, but it got less enjoyable as the field pack weighed down on my shoulders. I lasted a total of 10 back-breaking (pun intended) minutes in the chamber, which by my standards, was quite a feat.

Leading the way

Having visited three of DSO's many labs, I believe what I saw was probably a drop in the ocean of the many projects that its scientists are involved in. But the tours allowed me to better appreciate the work of defence scientists and researchers, and understand how their work helps to boost the SAF's fighting capabilities.

Since 1972, DSO has built up capabilities and expertise in areas such as guided systems, sensor systems, communications and chemical defence capabilities in support of homeland security.

The Skyblade III UAV which conducts surveillance and reconnaissance; CBRE (chemical, biological, radiological and explosives) robots that detect and decontaminate chemical threats; and exoskeleton systems that transfer a majority of a soldier's load to the ground are just some examples of products that have emerged in the past 40 years of research.

The next 40 years for DSO look set to be even more exciting.

Defence science revealed

Singapore's largest defence science exhibition will be held at the Science Centre from October 2012 to February 2013.

Jointly organised by DSO National Laboratories and Science Centre Singapore, the exhibition will showcase the use of defence science in the military through multimedia exhibits, interactive games and workshops.

Divided into three zones, the exhibition will introduce the technologies used in surveillance and stealth, flight as well as armour and protection. Besides learning how to evade enemy detection, visitors can experience the lift effect in a wind tunnel simulation, and find out how armoured vehicles withstand impact.

This exhibition is open to the public.

ALSO READ IN TECHNOLOGY

AI joins the fight in national cyber defence exercise

12 Nov 2025

AI and closer collaboration among agencies and industry are taking centre stage in this year’s Critical Infrastructure Defence Exercise (CIDeX).

They built this city

01 Oct 2025

Turning vision to reality: the team behind SAFTI City clinches the Defence Technology Prize 2025 Team (Engineering) Award!

Operating over skies & seas

22 Aug 2025

This gear is designed to help a Sensor Supervisor survive emergencies in the air and at sea.