TECHNOLOGY

DEEP SEA RESCUE

20 Oct 2010

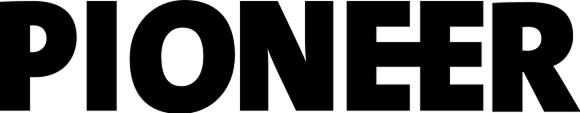

Six men, 70m under the sea. PIONEER packs off one of its writers to experience the Republic of Singapore Navy's (RSN's) Deep Search and Rescue 6 (DSAR 6) submersible - the only such submarine rescue capability of its kind in the Southeast Asian region.

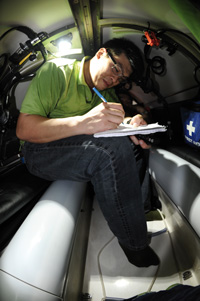

At first, it seemed like a bad joke - sending your largest writer who also happens to be hydrophobic, on an assignment that involved cramped spaces and diving to depths he cannot even begin to imagine.

That writer was me, and the confined space was within the DSAR 6. I stand at over 1.8m tall and weigh in at - dare I say - slightly less than 100kg. Imagine all of me in a square box of about 1.5m on each side, then add five more men each occupying about the same amount of space packed in shoulder-to-shoulder, and you can just start to imagine the conditions within the rescue chamber of the DSAR 6 that day.

The DSAR 6 has two compartments: the first is where the pilot and co-pilot sit, and the second, the rescue chamber, occupies the rest of the space within the 9.6m long submersible. Unfortunately for me, I was placed in the latter.

All this was arranged by the RSN as part of Exercise Pacific Reach, a regional Submarine Escape and Rescue (SMER) exercise which aims to develop SMER capabilities and enhance interoperability in submarine rescue operations among participating navies.

The RSN took part in this year's exercise, which was held from 17 to 25 Aug, along with the navies of Australia, Japan, the Republic of Korea and the United States. Military observers from 13 countries - Canada, China, France, India, Indonesia, Italy, Malaysia, Pakistan, South Africa, Sweden, Thailand, the United Kingdom and Vietnam - were also present.

Tight space

We entered through a small porthole one after another, and once we were all in, the Rescue Chamber Operator (RCO) hollered: "Everybody happy?" This was a call the six of us would hear quite often during our three-hour dive to meet the RSN's Challenger-class submarine RSS Chieftain, which was lying about 70m below us on the seabed.

With everyone crouched in a near-foetal position, the pilots and the RCO proceeded to conduct their safety checks while we tried to manage with the space we had. During that time, I received several elbows to various parts of my body and must have delivered some myself (sorry guys!). There was also an incident where I began to scratch my leg (or what I thought to be my leg), only to be greeted by my neighbour's rather startled face - that was how close we were to each other.

During actual rescue operations, the rescue chamber can pack in 17 submariners (all seated) or 11 submariners (nine seated, two lying down). It is certainly no luxury cruise, but when lives are at stake, comfort takes a back seat to survival.

Within the hour, we reached the simulated distressed submarine and the pilot announced that we were preparing to "mate" with the submarine. This is one of the most important steps in the entire rescue process.

Safety above all

Rescued submariners enter the DSAR 6 through a hatch at the bottom of the submersible. Before they can do so, the pilots and RCO on board the DSAR 6 perform a delicate operation which they term as "mating" with the submarine.

Besides ensuring that the seal between the two vessels is watertight before hatches on both sides are opened, the crew must adjust the atmospheric pressure within the DSAR 6 to that of the submarine, because a drastic difference could be fatal to those suffering from decompression sickness.

Similarly, when the DSAR 6 surfaces and docks with the recompression chamber located on the MV Swift Rescue, the atmospheric pressure level in the chamber will be adjusted to match that of the DSAR 6. The RSN is one of few in the world to possess this capability, which is called "Transfer Under Pressure".

With that key safety measure in place, all that is left is to transfer the distressed submariners from the submarine to the DSAR 6 and onto the MV Swift Rescue. The reality here is that one trip will never be enough as most submarines are manned by more than 17 people. This means the DSAR 6's three-man crew must work fast every step of the way.

Then it dawned on me: if even the oversized me could feel comfortable within that confined space, submariners should be more than happy to be rescued by the DSAR 6. And I didn't even get wet one bit during the entire three-hour dive. Piece of cake.

ALSO READ IN TECHNOLOGY

AI joins the fight in national cyber defence exercise

12 Nov 2025

AI and closer collaboration among agencies and industry are taking centre stage in this year’s Critical Infrastructure Defence Exercise (CIDeX).

They built this city

01 Oct 2025

Turning vision to reality: the team behind SAFTI City clinches the Defence Technology Prize 2025 Team (Engineering) Award!

Operating over skies & seas

22 Aug 2025

This gear is designed to help a Sensor Supervisor survive emergencies in the air and at sea.