A MINE-BLOWING EXPERIENCE

STORY // Teo Jing Ting

PHOTO // PIONEER Photographers & Courtesy of RSN

What happens if a sea mine lurks beneath our waters? Then it's time to call upon the Navy's Mine Counter-Measure Vessels (MCMVs).

Singapore has always been heavily dependent on maritime trade. The Port of Singapore is ranked the second-busiest port in the world, with more than 1,000 ships passing through its waters every day.

But beneath the waters, potential threats lurk. Mines as old as the ones left over from World War II may lie on the seabed. These pose a risk to ships and could cause great damage to both the shipping trade and human lives.

This is where the Republic of Singapore Navy's (RSN's) MCMVs come in. They may not look as grand as the Landing Ships Tank or Frigates, but are exceptional at their job of hunting down mines.

Smarter sonars

Their capabilities have also been enhanced by recent upgrades such as those made to the Mine Hunting Sonar (MHS), which has been in use for 15 years.

The "eye" of the MCMV, the MHS is hull-mounted and lowered through the keel to scan for mine-like objects in the water. Compared to its previous version, the upgraded MHS scans twice as deep and as wide, providing a much clearer picture of underwater objects.

Major (MAJ) Ng Chee Wee, Commanding Officer of RSS Punggol, added that the new MHS has various frequency modes to support the needs of different mine-hunting missions.

"The higher the frequency, the better the survey resolution is, but at a lower coverage rate. Being able to choose the frequency therefore allows us to adjust the sonar to operational needs."

Unlike its hull-mounted counterpart, the Towed Synthetic Aperture Sonar (TSAS) works by being towed from the back of the MCMV.

With the ability to go as close as just a few metres above the seabed, the TSAS's parallel scanning methods enable the operators to get an even clearer picture of objects

than the MHS.

When operating the MHS, an operator has to keep a watchful eye in case the sonar hits something in its path. The TSAS, however, is equipped with sensors for it to react accordingly when it senses an obstruction.

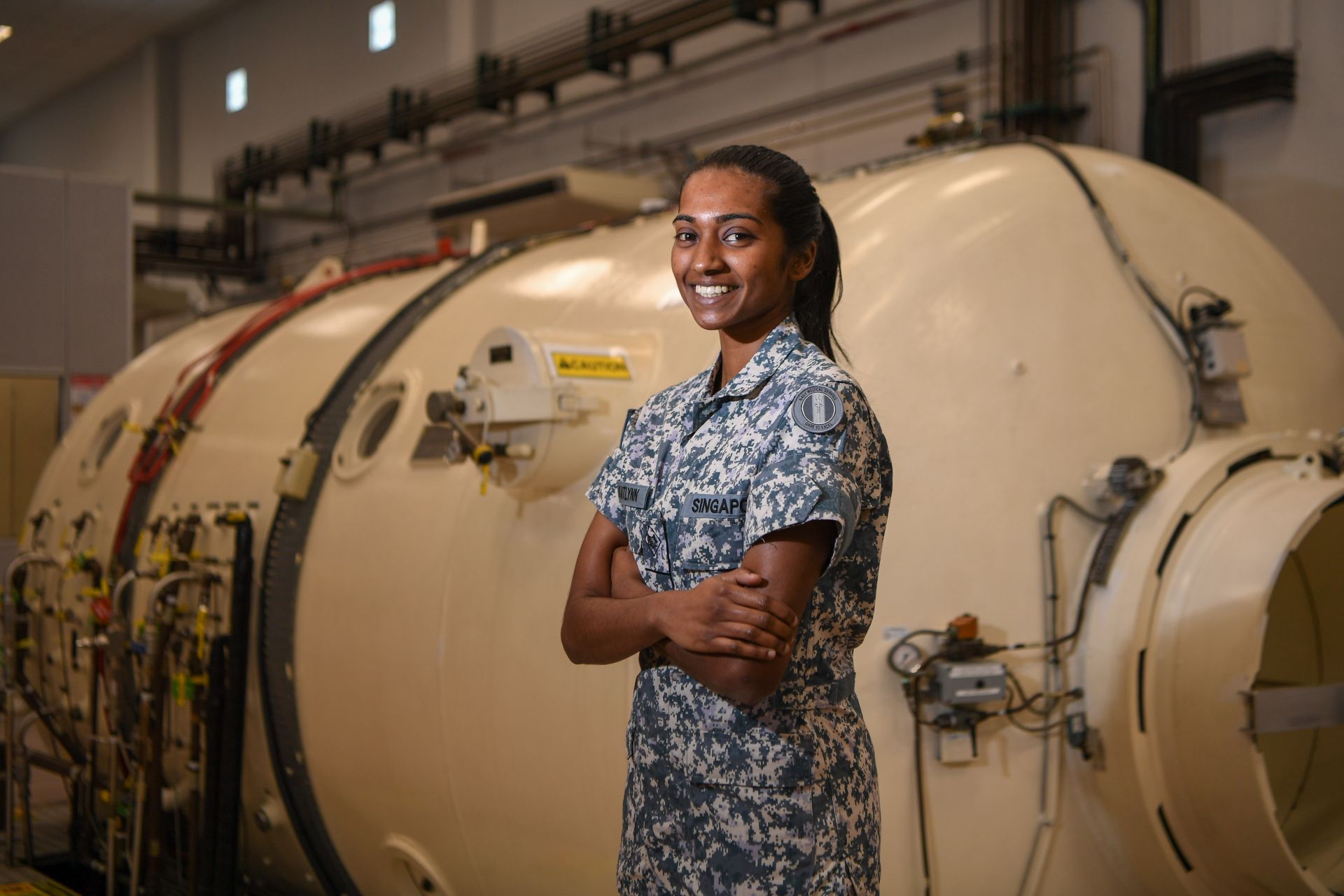

Military Expert (ME) 2 Briane Vivaegananthan explained: "If it (the TSAS) senses that it's going to hit something, it will automatically rise above the object to avoid it."

The 33-year-old Mine Disposal Systems Supervisor from RSS Bedok added that the TSAS also provides sonar readings in colour.

An average sonar such as the MHS usually produces black and white readings on a screen, and an operator has to be well-trained before he is able to pick out and identify a mine-like object from those readings.

Another advantage of the TSAS is that it comes with a handy library that provides a list of possible objects based on the dimensions of the sonar readings.

This helps even the most inexperienced operator to better identify objects that the sonar picks up from the seabed.

Explained ME2 Briane: "For instance, if the sonar picks up an object with 1m x 2m dimensions, the system will pull out a series of possibilities. It might show that this object has a 30 percent possibility of being a sofa or perhaps, a 90 percent chance of being a mine-like contact.

"Based on these probabilities and the options given, an operator can better decide the appropriate action to take."

"The recent enhancements to the MCMVs have improved the ships' mine-hunting capabilities and boosted the crew's morale."

- Maj Ng

Two methods, quicker scans

As mine hunting is a slow and tedious process, having both the TSAS and the MHS means that the MCMVs now have two ways to locate mines. This allows the crew to do it at a much faster pace.

The two sonars are deployed, depending on the distance of the mine-hunting route, as well as the depth of scanning.

When operating the TSAS, there should be sufficient sea room as the TSAS needs to be towed behind the ship for it to be streamed out properly, said MAJ Ng.

Although the TSAS takes longer than the MHS to be deployed, its scanning speed makes up for any time lost during preparation.

The TSAS allows the MCMV to survey the seabed at almost twice the speed of the upgraded MHS.

On the other hand, the MHS is typically deployed in confined areas, such as a narrow strait or where water depths are generally shallower. This allows the crew to quickly deploy, scan and recover, and move on to another mission.

Best of both worlds

Having two sonars on board the same ship also provides an opportunity for them to work in tandem. When the TSAS is deployed, it becomes the main sonar while the MHS acts as a lookout for mid-water obstacles.

"With the TSAS trawling at the back of the ship, you need to constantly look ahead to make sure that there are no mid-water objects which might snag onto the TSAS," said MAJ Ng.

This method of surveying makes the mine-hunting process twice as fast as compared to the past.

The introduction of the TSAS also enables the crew to explore innovative tactics, such as the simultaneous deployment of two MCMVs in a "sensor-shooter" concept.

The ship in the front - the sensor - makes use of the TSAS to rapidly survey and detect mine-like objects, while the ship in the rear - the shooter - takes a closer look to identify if the suspicious object is really a mine before blowing it up if necessary.

MAJ Ng explained: "Upon finding a possible mine, the TSAS operator on the sensor ship will convey this information to the shooter ship via geo-referenced data linkages."

To perform a detailed classification of an underwater object, the MCMV has to physically move around in order for the MHS to have a 360-degree perspective of a detected object, such as its shape, size and shadow.

If the object is found to be mine-like, an operator from the shooter ship can launch the K-STER Expendable Mine Disposal System (EMDS) to neutralise the mine.

It's da bomb

A remotely operated vehicle, the K-STER EMDS is one of the new upgrades the MCMVs have received. It comes in two variants: I (which stands for identification) and C (which stands for clearance).

Before a mine is destroyed, the crew needs to make sure that its detonation is absolutely necessary. The K-STER operator will launch the K-STER I, which is equipped with a camera for live video streaming and a sonar to provide greater clarity even in low visibility waters, such as those in Singapore.

If the object is identified to be a mine, the K-STER I is recovered and the operator will launch the K-STER C, which is filled with ammunition, to detonate the object.

The crew can launch the 50kg K-STER three times faster than its predecessor, the Mine Disposal Vehicle (MDV) which weighs more than 300kg. In addition, an MDV requires three people to launch whereas the K-STER needs just one person.

As there were no variants for the MDV, the entire process took much longer in the past launching it first for identification, bringing it back to the ship and filling it with charge, before launching the vehicle once more for detonation.

Having it upgraded to the K-STER thus amounted to more than 70 percent in time savings.

More often than not, when it comes to the decision of whether to blow up sea mines, the maxim is to "avoid if we can, clear if we must", said MAJ Ng. If a mine is identified but there is sea room for route deviation, the crew of the MCMVs will identify and recommend an alternative passage for ships to take. It could be a solution as simple as just changing lanes 50m to the right.

"Blowing up a mine takes time. In channel clearance missions, the priority is to open up a safe passage as fast as possible," explained MAJ Ng. "However, if the mine is in an unavoidable area and we have no choice but to clear it, we will."

Embracing unmanned technology

Many modern navies have moved into the area of unmanned technology, and the RSN is no exception. Its latest and most important addition to the MCMVs is proof that the Navy is keeping up with the times.

Called the Remote Environmental Monitoring Units (REMUS), this autonomous underwater vessel is a combination of both the MHS and TSAS.

This lightweight portable system is launched from a sea boat or Rigid-Hull Inflatable Boat (RHIB), and can be deployed in areas that the MCMV is unable to enter, such as restricted areas and shallow waters.

Weighing about 37kg, it can be launched by a four-man team. Among them is ME3 Tan Chee Kong, Chief Unmanned Systems (Underwater) from 194 Squadron (SQN). "The beauty of having a REMUS is that we can do our job of hunting mines without the need for our men to step into the minefield," said ME3 Tan.

He explained that the REMUS can be deployed from a remote location: The unmanned vessel will follow the tracks that the team has planned and scan the seabed with its sonar before returning to the boat. ME3 Tan and his team will then download and analyse the data collected.

As the REMUS does not provide real-time feedback, careful planning of its route is required before it is launched.

"After we launch it from the sea boat, we track its progress via a handheld GPS to make sure that it doesn't get lost or run into any objects," said the 37-year-old.

Unlike most sonar capabilities which tend to be bulky, the REMUS is small and portable. This makes it particularly useful as an added underwater search capability, easily transported from one ship to another.

Head Unmanned Systems (Underwater) MAJ Teng Teck Hong explained: "The benefit of the REMUS is that if you have a ship that doesn't have underwater search capabilities, it can be brought on board. The REMUS can also be flown via planes, so wherever you need us, you can fly us there."

The 39-year-old added that having the REMUS helped to cut down on manpower requirements. "It is more efficient because we're sending the REMUS out with just four men, compared to sending out a ship with a crew of 30."

Underwater search

And when it comes to search and locate operations, the REMUS has proven to be a great asset.

This was demonstrated when MAJ Teng, ME3 Tan and two others were deployed, together with the REMUS, to help in the search for the missing AirAsia flight QZ8501 last December.

The team of four was placed on MV Swift Rescue to assist in operations with the REMUS's underwater search capability. It took them six hours to fly there and to be deployed. An MCMV, on the other hand, would have taken three days.

As they were tasked to look for aircraft wreckage, MAJ Teng and his team studied the profile of the aircraft and wreckage pictures that they found from the Internet prior to their deployment.

"We made an assessment of how the wreckage would look like underwater so that we could roughly know what we were looking for. We would then match it with the data collected by the sonar and try to interpret them to see if they were similar."

While they were there, poor weather and bad sea states hampered their operations as they had to launch the REMUS from a small boat and risked the possibility of being engulfed by high waves.

Despite these conditions, the REMUS team managed to help shorten the time taken to complete searching the assigned sector.

Another ship deployed in aid of the AirAsia tragedy was RSS Kallang, which set sail on 31 Dec 2014 as part of the Underwater Search Task Group.

The K-STER EMDS on board RSS Kallang aided the crew and other search teams greatly in their searches, providing a clearer view of underwater objects, said MAJ Teng.

"The MHS was first used to scan the seabed for wreckages... If an object was spotted, the crew would launch the K-STER to take a closer look, as the video camera function on the K-STER provided a much clearer image of the object in question."

RSS Kallang was out at sea for close to two weeks.

Moving forward

For 194 SQN and the MCMVs, eliminating threats under the sea and ensuring that the sea lanes are clear of mines will always be their primary mission, no matter how arduous and long the process may be.

The recent upgrades have breathed new life into the ships, which were commissioned in 1995. They have also been a morale booster to the MCMV crew, allowing them to operate more efficiently and focus more on getting the mission done.

"In the past, I might need 24 hours to clear a certain area. I can do so now in half that time with a greater level of confidence, as my sonars are much more effective," said MAJ Ng.

He added: "Our slogan is 'Safe in our wake', meaning that where an MCMV has been, it is safe to follow behind. 194 SQN may be a relatively small unit, but one with a niche capability that has a huge significance.

"Mine-countering is a very specialised area of expertise, and nobody else in Singapore has this capability except us."

Did you know?

- The first ship of its class (the Bedok-class MCMV), RSS Bedok, was commissioned in 1995.

- The MCMVs were named after coastal towns in Singapore. It is a worldwide tradition for MCMVs to be named after coastal towns. Bedok, Kallang, Punggol and Katong happened to be the four coastal towns in Singapore, before reclamation was done.

- The hull of the MCMV is made of plastic. The MCMV is made of Glass-Reinforced Polyester, commonly known as fibre-glass. As mines are mainly designed to target ships, which are essentially big pieces of floating steel, a plastic hull prevents the MCMV from emitting the typical metallic signature which would trigger mines.

- The MCMVs' proportions are similar to those of commercial tugboats. This allows the MCMVs to be highly manoeuvrable so that they can easily weave in and out of hard-to-access areas while scanning for sea mines.

Upgrades List

Check out some of the upgrades and new technology that boost the MCMV's operational capabilities.

25mm Typhoon Naval Stabilised Gun System

Replacing the 40mm BOFORS L70 gun, the Typhoon gun fires more accurately and puts the crew at less risk as it can be operated remotely from within the ship. As the MCMV is not typically used for naval battles, the gun is to help defend it against small boat attacks.

Mine Hunting Sonar (MHS)

The eye of the MCMV, the MHS is hull-mounted and lowered through the keel to scan for mine-like objects in the water. The upgraded MHS scans twice as deep and twice as wide compared to its predecessor, providing a much clearer picture of underwater objects.

K-STER Expendable Mine Disposal System (EMDS)

This remotely operated vehicle replaces its predecessor, the Mine Disposal Vehicle. The K-STER EMDS consists of two variants: the K-STER I and K-STER C. Equipped with a camera for live video streaming and a sonar, the K-STER I is mainly used to take a closer look at a mine-like object before a decision is made whether to blow it up. In this case, the K-STER C will be activated.

Towed Synthetic Aperture Sonar (TSAS)

This yellow torpedo-like sonar works by being towed from the back of the MCMV. The TSAS has a wider detection range and can scan as close as just as a few metres above the seabed, allowing the MCMV to carry out underwater surveys at a much faster speed. Other advantages of the TSAS include being equipped with sensors to react accordingly when it senses obstructions, and providing sonar readings in colour. It often works in tandem with the MHS.

Remote Environmental Monitoring Units (REMUS)

This autonomous underwater vessel is an unmanned sonar which is launched from a sea boat or Rigid-Hull Inflatable Boat. It can be deployed in areas that the MCMV is unable to enter, such as restricted areas and shallow waters.

Small and portable, the REMUS is useful as an added underwater search capability, easily transported by flight or from one ship to another. Its unmanned capability minimises the risk to human lives, eliminating the need for personnel to step into the minefield to hunt for mines.

Since 2011, the REMUS has been taking part in an annual international mine counter-measure exercise held in Bahrain. These exercises provide exposure and enable the REMUS team to learn from and benchmark themselves against their United States and Australian counterparts. The REMUS was also involved in the search and locate operations for the missing AirAsia flight QZ8501 last December.

.jpg?sfvrsn=b5383902_1)

.jpg?sfvrsn=4eb1b86e_1)